Teaching At ALTIS: My Lessons Learned From The Residential Week

Aug 13

/

Denis Logan

Introduction:

The Convergence of Teaching and Learning

Let me share something that's become increasingly clear to me over the years: the moment you think you've mastered coaching is precisely when you stop being an effective coach.

This isn't just philosophical musings—it's grounded in what educational psychologists call the "expert blind spot," where deep expertise can actually impair our ability to see problems from fresh perspectives.

Last week at ALTIS, one of the world's premier athletic performance facilities, I experienced this principle in action while leading two intensive days of workshops with master's-level strength and conditioning students.

The experience reinforced a fundamental truth about performance coaching: our field isn't static.

It's a dynamic interplay between scientific advancement, practical application, and continuous refinement of our observational and decision-making processes.

What made these sessions particularly valuable wasn't just the content we covered—though we dove deep into athlete profiling methodologies, plyometric progression frameworks, eccentric utilization ratios, dynamic strength indices, and load-velocity profiling systems.

The real insights emerged from the spaces between formal instruction, during those impromptu discussions with fellow coaches and mentors where theory meets reality. These conversations illuminated something I've been advocating for years but saw with renewed clarity: systematic approaches to coaching aren't constraints on creativity—they're the foundation that enables it.

Think about it this way: would you trust a surgeon who "just wings it" based on intuition?

Of course not. Yet in performance coaching, we sometimes fall into the trap of believing that structure somehow diminishes the art of what we do.

The reality is quite the opposite.

This isn't just philosophical musings—it's grounded in what educational psychologists call the "expert blind spot," where deep expertise can actually impair our ability to see problems from fresh perspectives.

Last week at ALTIS, one of the world's premier athletic performance facilities, I experienced this principle in action while leading two intensive days of workshops with master's-level strength and conditioning students.

The experience reinforced a fundamental truth about performance coaching: our field isn't static.

It's a dynamic interplay between scientific advancement, practical application, and continuous refinement of our observational and decision-making processes.

What made these sessions particularly valuable wasn't just the content we covered—though we dove deep into athlete profiling methodologies, plyometric progression frameworks, eccentric utilization ratios, dynamic strength indices, and load-velocity profiling systems.

The real insights emerged from the spaces between formal instruction, during those impromptu discussions with fellow coaches and mentors where theory meets reality. These conversations illuminated something I've been advocating for years but saw with renewed clarity: systematic approaches to coaching aren't constraints on creativity—they're the foundation that enables it.

Think about it this way: would you trust a surgeon who "just wings it" based on intuition?

Of course not. Yet in performance coaching, we sometimes fall into the trap of believing that structure somehow diminishes the art of what we do.

The reality is quite the opposite.

The Critical Need for Systematic Coaching Frameworks

Understanding the Problem: Navigating Without a Map

Here's a scenario I've witnessed countless times: a talented coach with excellent instincts makes brilliant individual training decisions but struggles to articulate why those decisions work or replicate that success consistently across different athletes.

It's like being a naturally gifted musician who plays beautifully by ear but can't read music—impressive in isolation, limiting at scale. Without a coherent framework guiding your coaching decisions, you're essentially navigating a complex metropolitan area without GPS, street signs, or even a basic map. Sure, you might eventually reach your destination through trial and error, but consider what you lose in the process: time, efficiency, opportunities for optimization, and perhaps most critically, the ability to teach others your methods or collaborate effectively within a performance team.

The absence of systematic approaches creates several cascading problems.

First, there's the issue of cognitive load.

When every decision requires starting from scratch, you're exhausting mental resources that could be better allocated to observation and adaptation.

Second, there's the challenge of communication.

How do you explain your programming choices to athletes, other coaches, or support staff without a common language and framework?

Third, and perhaps most overlooked, is the problem of professional development.

How do you improve at something you can't measure or systematically analyze?

It's like being a naturally gifted musician who plays beautifully by ear but can't read music—impressive in isolation, limiting at scale. Without a coherent framework guiding your coaching decisions, you're essentially navigating a complex metropolitan area without GPS, street signs, or even a basic map. Sure, you might eventually reach your destination through trial and error, but consider what you lose in the process: time, efficiency, opportunities for optimization, and perhaps most critically, the ability to teach others your methods or collaborate effectively within a performance team.

The absence of systematic approaches creates several cascading problems.

First, there's the issue of cognitive load.

When every decision requires starting from scratch, you're exhausting mental resources that could be better allocated to observation and adaptation.

Second, there's the challenge of communication.

How do you explain your programming choices to athletes, other coaches, or support staff without a common language and framework?

Third, and perhaps most overlooked, is the problem of professional development.

How do you improve at something you can't measure or systematically analyze?

The Power of Frameworks in Action

During my time at ALTIS, I observed how even highly experienced coaches—people with decades in the field—benefited from revisiting and refining their systematic approaches.

It's not about rigidity; it's about having a robust scaffolding that supports decision-making while allowing for contextual adaptation.

The framework doesn't eliminate coaching judgment—it enhances it by providing objective data to inform subjective decisions.

This principle extends across all aspects of performance coaching. When your process is clear and systematic, several things happen:

your decisions become faster because you're not starting from zero each time;

your athletes improve more efficiently because interventions are targeted rather than shotgun approaches;

your team functions better because everyone understands the rationale behind programming decisions; and perhaps most importantly,

you create a feedback loop for continuous improvement because you have clear metrics and processes to evaluate.

It's not about rigidity; it's about having a robust scaffolding that supports decision-making while allowing for contextual adaptation.

The framework doesn't eliminate coaching judgment—it enhances it by providing objective data to inform subjective decisions.

This principle extends across all aspects of performance coaching. When your process is clear and systematic, several things happen:

your decisions become faster because you're not starting from zero each time;

your athletes improve more efficiently because interventions are targeted rather than shotgun approaches;

your team functions better because everyone understands the rationale behind programming decisions; and perhaps most importantly,

you create a feedback loop for continuous improvement because you have clear metrics and processes to evaluate.

Core Lessons from ALTIS:

Three Paradigm-Shifting Insights

1. The Perception-Reaction Dichotomy:

Rethinking Agility Training with Rich Clarke

One of the most profound insights from the workshop came during a discussion, and following practical sessions, with Rich Clarke about the fundamental difference between reaction and perception in athletic performance.

This distinction isn't merely semantic—it has massive implications for how we structure agility and reactive training.

Traditional agility training often focuses on reaction: athletes respond to predetermined stimuli like whistles, lights, or verbal commands. We set up elaborate light systems, use apps that flash colors, blow whistles at random intervals.

And yes, these methods can improve reaction time in controlled conditions. But here's the critical question: how often in actual competition does an athlete respond to a whistle or a flashing light that tells them exactly where to go?

This same question was asked during the course that elicited a chuckle and response from the track and field coaches...

"Always"...

But i think they were getting the point in a sporting context.

The answer, of course, is almost never.

In field sports (open skill), athletes aren't reacting to abstract signals—they're perceiving and interpreting complex, dynamic information from opponents, teammates, and the evolving tactical situation.

A basketball defender doesn't cut left because a light told them to; they read the subtle shift in an opponent's hips, the angle of their shoulders, the position of their planted foot.

A soccer midfielder doesn't change direction based on a whistle; they anticipate space opening based on the movement patterns of multiple players simultaneously.

This distinction between reaction and perception demands a fundamental shift in how we approach agility training.

It also has begun to reorganize the way I talk about Open vs Closed Skills and drills.

I have (as has most of the industry) referred to and defined closed skills/drills as those that don't require reaction.

With Rich's very powerful distinction, I believe it's more appropriate (and accurate) to say that Closed Drills don't require perception.

Instead of isolated reaction drills, we need to incorporate what could be labeled as "representative learning environments"—training scenarios that include the perceptual information athletes actually use in competition.

This means more small-sided games where athletes must read and respond to opponents.

It means using live defenders in change-of-direction drills rather than cones.

It means creating decision-making scenarios under pressure where the "correct" response isn't predetermined but emerges from reading the situation.

Consider the practical implications: instead of having a footballer react to colored cones in a predetermined pattern, you might have them respond to an actual opponent's movement.

The opponent might show certain postural cues—a dropped shoulder, a shifted center of mass—that the athlete must perceive and interpret in real-time.

Rich took the group through a number of these types of drills on Day 3 and it was amazing to see the learning that was taking place in real time...plus the exclamations of "this is hard!".

This isn't just more game-like; it's training the actual neurological pathways and decision-making processes that determine performance in competition.

The research supports this approach.

Studies on ecological dynamics and constraints-led coaching show that when training includes representative perceptual information, transfer to performance is significantly higher.

It's not enough to be fast; athletes need to be fast in response to the right stimuli, making the right decisions based on accurate perception of relevant information.

This distinction isn't merely semantic—it has massive implications for how we structure agility and reactive training.

Traditional agility training often focuses on reaction: athletes respond to predetermined stimuli like whistles, lights, or verbal commands. We set up elaborate light systems, use apps that flash colors, blow whistles at random intervals.

And yes, these methods can improve reaction time in controlled conditions. But here's the critical question: how often in actual competition does an athlete respond to a whistle or a flashing light that tells them exactly where to go?

This same question was asked during the course that elicited a chuckle and response from the track and field coaches...

"Always"...

But i think they were getting the point in a sporting context.

The answer, of course, is almost never.

In field sports (open skill), athletes aren't reacting to abstract signals—they're perceiving and interpreting complex, dynamic information from opponents, teammates, and the evolving tactical situation.

A basketball defender doesn't cut left because a light told them to; they read the subtle shift in an opponent's hips, the angle of their shoulders, the position of their planted foot.

A soccer midfielder doesn't change direction based on a whistle; they anticipate space opening based on the movement patterns of multiple players simultaneously.

This distinction between reaction and perception demands a fundamental shift in how we approach agility training.

It also has begun to reorganize the way I talk about Open vs Closed Skills and drills.

I have (as has most of the industry) referred to and defined closed skills/drills as those that don't require reaction.

With Rich's very powerful distinction, I believe it's more appropriate (and accurate) to say that Closed Drills don't require perception.

Instead of isolated reaction drills, we need to incorporate what could be labeled as "representative learning environments"—training scenarios that include the perceptual information athletes actually use in competition.

This means more small-sided games where athletes must read and respond to opponents.

It means using live defenders in change-of-direction drills rather than cones.

It means creating decision-making scenarios under pressure where the "correct" response isn't predetermined but emerges from reading the situation.

Consider the practical implications: instead of having a footballer react to colored cones in a predetermined pattern, you might have them respond to an actual opponent's movement.

The opponent might show certain postural cues—a dropped shoulder, a shifted center of mass—that the athlete must perceive and interpret in real-time.

Rich took the group through a number of these types of drills on Day 3 and it was amazing to see the learning that was taking place in real time...plus the exclamations of "this is hard!".

This isn't just more game-like; it's training the actual neurological pathways and decision-making processes that determine performance in competition.

The research supports this approach.

Studies on ecological dynamics and constraints-led coaching show that when training includes representative perceptual information, transfer to performance is significantly higher.

It's not enough to be fast; athletes need to be fast in response to the right stimuli, making the right decisions based on accurate perception of relevant information.

2. The Progressive Observational Framework:

Dan Pfaff's Systematic Approach to Movement Analysis

Dan Pfaff, one of the most successful track and field coaches in history, shared a methodology that transformed how I think about developing observational skills.

It's a systematic approach he learned from his own mentor, and it addresses one of the biggest challenges in coaching: information overload during movement observation.

When you watch an athlete perform—whether it's a sprint, a jump, or a complex sporting movement—there's simply too much happening for the human brain to process simultaneously.

Joint angles, velocities, timing, coordination patterns, force application, postural control—it's an overwhelming amount of information occurring in fractions of seconds.

Most coaches respond to this challenge in one of two ways: they either try to see everything at once (and consequently see nothing clearly), or they default to watching whatever seems most obvious or problematic (and miss subtle but crucial details).

Pfaff's framework provides a third way: systematic, progressive observation that builds complexity over time.

Here's how it works in practice: Start by selecting a single body segment—let's say the right foot—and watch only that segment for an entire set of repetitions.

Notice its position at contact, the angle of dorsiflexion, how it interacts with the ground, the timing of toe-off.

Ignore everything else...

your entire attention is on that single segment.

Next set, shift your focus to the corresponding segment on the opposite side—the left foot. Apply the same intense, focused observation.

Then, on the third set, watch how both feet work together.

Are they symmetrical?

Is there a timing difference?

Does one pronate more than the other?

Once you've mastered observation at this level, move up the kinetic chain.

Spend sets watching just the ankle, then both ankles, then the relationship between feet and ankles. Progress to the knees, then hips, observing each in isolation before examining their integration.

This approach does several things.

First, it trains your observational focus, teaching you to maintain attention on specific details rather than being distracted by global movement.

Second, it builds a mental library of movement patterns. After watching hundreds of right feet during acceleration, you develop an intuitive sense for what efficient and inefficient patterns look like.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, it develops your ability to see relationships between segments—how dysfunction at the foot might manifest as compensation at the hip, or how limited ankle mobility might alter entire movement strategies.

The framework also addresses the developmental trajectory of coaching expertise.

Novice coaches using this system learn to see details they would otherwise miss. Experienced coaches use it to maintain and sharpen their observational skills, preventing the complacency that can come with experience.

It's a deliberate practice approach to developing what we might call the "coach's eye"—that seemingly intuitive ability to spot movement inefficiencies that actually comes from thousands of hours of systematic observation.

It's a systematic approach he learned from his own mentor, and it addresses one of the biggest challenges in coaching: information overload during movement observation.

When you watch an athlete perform—whether it's a sprint, a jump, or a complex sporting movement—there's simply too much happening for the human brain to process simultaneously.

Joint angles, velocities, timing, coordination patterns, force application, postural control—it's an overwhelming amount of information occurring in fractions of seconds.

Most coaches respond to this challenge in one of two ways: they either try to see everything at once (and consequently see nothing clearly), or they default to watching whatever seems most obvious or problematic (and miss subtle but crucial details).

Pfaff's framework provides a third way: systematic, progressive observation that builds complexity over time.

Here's how it works in practice: Start by selecting a single body segment—let's say the right foot—and watch only that segment for an entire set of repetitions.

Notice its position at contact, the angle of dorsiflexion, how it interacts with the ground, the timing of toe-off.

Ignore everything else...

your entire attention is on that single segment.

Next set, shift your focus to the corresponding segment on the opposite side—the left foot. Apply the same intense, focused observation.

Then, on the third set, watch how both feet work together.

Are they symmetrical?

Is there a timing difference?

Does one pronate more than the other?

Once you've mastered observation at this level, move up the kinetic chain.

Spend sets watching just the ankle, then both ankles, then the relationship between feet and ankles. Progress to the knees, then hips, observing each in isolation before examining their integration.

This approach does several things.

First, it trains your observational focus, teaching you to maintain attention on specific details rather than being distracted by global movement.

Second, it builds a mental library of movement patterns. After watching hundreds of right feet during acceleration, you develop an intuitive sense for what efficient and inefficient patterns look like.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, it develops your ability to see relationships between segments—how dysfunction at the foot might manifest as compensation at the hip, or how limited ankle mobility might alter entire movement strategies.

The framework also addresses the developmental trajectory of coaching expertise.

Novice coaches using this system learn to see details they would otherwise miss. Experienced coaches use it to maintain and sharpen their observational skills, preventing the complacency that can come with experience.

It's a deliberate practice approach to developing what we might call the "coach's eye"—that seemingly intuitive ability to spot movement inefficiencies that actually comes from thousands of hours of systematic observation.

3. The Power of Role Clarity:

Optimizing Performance Support Teams

The third major insight from ALTIS relates to something we often overlook in our pursuit of comprehensive athlete development: the critical importance of staying in your lane within a performance support team.

This isn't about limitation—it's about optimization.

There's a seductive trap in performance coaching, particularly as you gain experience and expand your knowledge base.

You start as a strength coach, then learn about nutrition, then pick up some physical therapy techniques, maybe dive into sports psychology. Before you know it, you're trying to be everything to your athletes—coach, nutritionist, therapist, psychologist, and friend.

It feels like comprehensive care, but it's actually a recipe for mediocrity and burnout.

The research on high-performing teams, whether in sport, business, or healthcare, consistently shows that role clarity is one of the strongest predictors of team effectiveness. When team members understand their specific responsibilities, areas of expertise, and boundaries, several positive outcomes emerge:

communication improves because everyone knows who to consult for what;

decision-making accelerates because there's no ambiguity about who has authority in specific domains;

and perhaps most importantly, trust increases because team members can rely on others to execute their roles with expertise.

This might seem obvious, but in practice, it's surprisingly difficult to maintain. There's ego involved—we want to be seen as knowledgeable and helpful.

There's convenience—it's easier to give quick advice than coordinate with another professional.

And there's the athlete's perspective—they often prefer getting everything from one trusted source rather than navigating multiple relationships. But here's what I've learned: when you try to be everything, you dilute your core expertise.

The time you spend becoming marginally competent in peripheral areas is time not spent achieving excellence in your primary domain.

Moreover, you might inadvertently provide suboptimal or even harmful advice outside your expertise.

A strength coach giving detailed nutritional guidance without proper education might miss critical interactions with medications or underlying health conditions.

A sport coach attempting psychological interventions might inadvertently worsen anxiety or other mental health challenges.

The solution isn't isolation—it's intelligent collaboration.

This means knowing enough about adjacent fields to communicate effectively with specialists, recognize when their expertise is needed, and integrate their recommendations into your programming.

It means developing what I call "collaborative competence"—the ability to work effectively within a multidisciplinary team while maintaining clear professional boundaries.

This isn't about limitation—it's about optimization.

There's a seductive trap in performance coaching, particularly as you gain experience and expand your knowledge base.

You start as a strength coach, then learn about nutrition, then pick up some physical therapy techniques, maybe dive into sports psychology. Before you know it, you're trying to be everything to your athletes—coach, nutritionist, therapist, psychologist, and friend.

It feels like comprehensive care, but it's actually a recipe for mediocrity and burnout.

The research on high-performing teams, whether in sport, business, or healthcare, consistently shows that role clarity is one of the strongest predictors of team effectiveness. When team members understand their specific responsibilities, areas of expertise, and boundaries, several positive outcomes emerge:

communication improves because everyone knows who to consult for what;

decision-making accelerates because there's no ambiguity about who has authority in specific domains;

and perhaps most importantly, trust increases because team members can rely on others to execute their roles with expertise.

This might seem obvious, but in practice, it's surprisingly difficult to maintain. There's ego involved—we want to be seen as knowledgeable and helpful.

There's convenience—it's easier to give quick advice than coordinate with another professional.

And there's the athlete's perspective—they often prefer getting everything from one trusted source rather than navigating multiple relationships. But here's what I've learned: when you try to be everything, you dilute your core expertise.

The time you spend becoming marginally competent in peripheral areas is time not spent achieving excellence in your primary domain.

Moreover, you might inadvertently provide suboptimal or even harmful advice outside your expertise.

A strength coach giving detailed nutritional guidance without proper education might miss critical interactions with medications or underlying health conditions.

A sport coach attempting psychological interventions might inadvertently worsen anxiety or other mental health challenges.

The solution isn't isolation—it's intelligent collaboration.

This means knowing enough about adjacent fields to communicate effectively with specialists, recognize when their expertise is needed, and integrate their recommendations into your programming.

It means developing what I call "collaborative competence"—the ability to work effectively within a multidisciplinary team while maintaining clear professional boundaries.

Deep Dive into Workshop Content:

Practical Applications of Performance Assessment

Athlete Profiling: Beyond Basic Testing

Write your awesome label here.

Write your awesome label here.

Write your awesome label here.

Write your awesome label here.

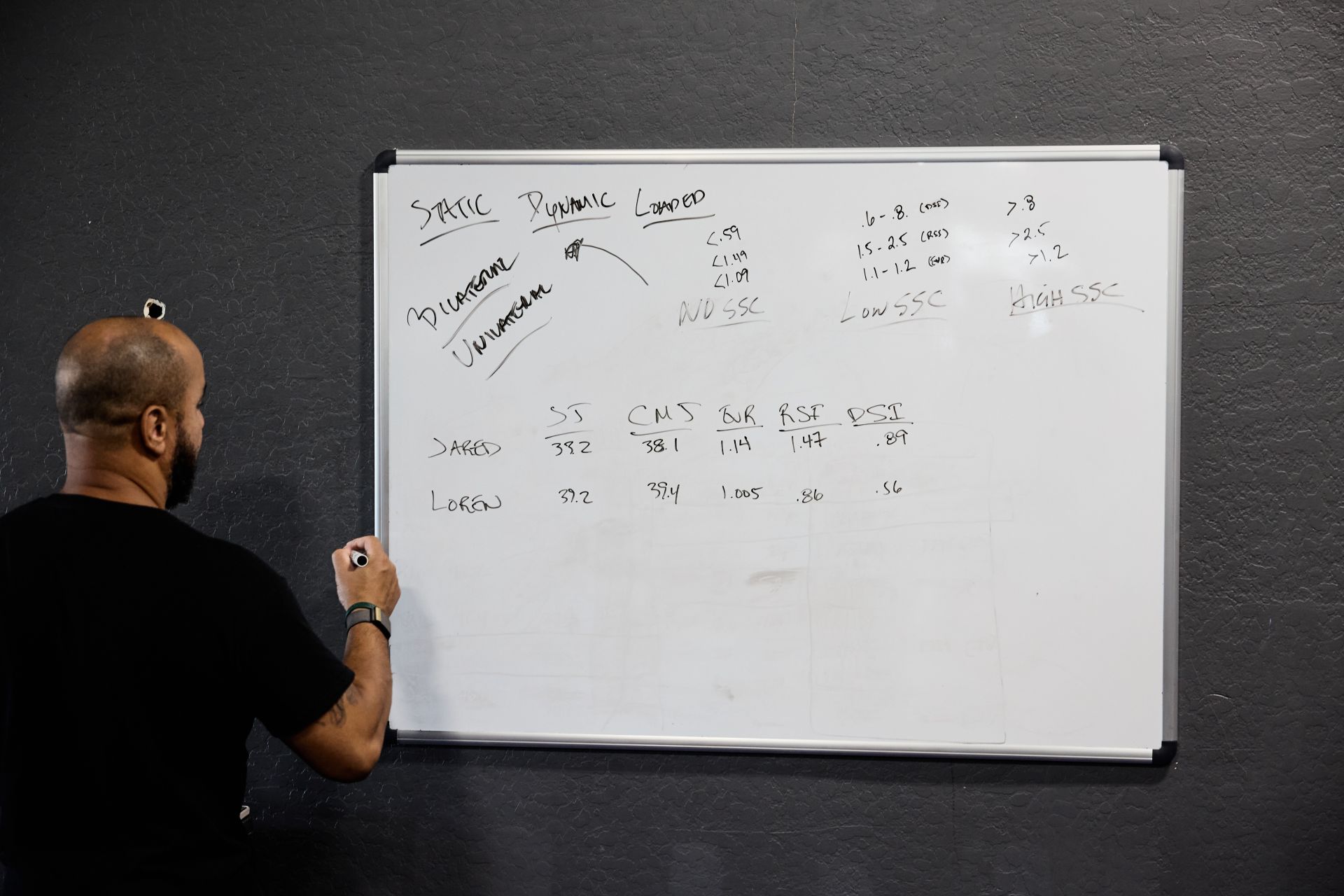

The athlete profiling sessions at ALTIS went far beyond traditional performance testing.

We explored how to use assessments not just to collect numbers, but to build comprehensive pictures of athletic capabilities and limitations that directly inform programming decisions.

The foundation starts with jump testing, but not just any jump testing—systematic assessment using multiple jump variations to understand different qualities.

We used basic force deck outputs including jump height, peak force, and reactive strength index (RSI), but the magic isn't in the individual numbers—it's in understanding their relationships.

For instance, comparing an athlete's squat jump (no countermovement) to their countermovement jump tells you about their ability to utilize the stretch-shortening cycle. If the difference is minimal, that athlete likely needs work on elastic/reactive qualities.

If the difference is large, they're already efficient at using stored elastic energy and might benefit more from pure strength development.

Emphasis on the word "might" is important because depending on the context (what sport does this person play) then general assumptions will likely change.

However, the data serves to elicit and lead that conversation so that the appropriate approach is discovered.

Movement dominance assessment was another crucial component.

Looking at what the intuitive "movement strategy" of the athlete played a role in:

A) understanding their default programming and

B) whether the shapes they chose were bio-mechanically efficient for the tasks that they were charged with.

We examined whether athletes are knee-dominant or hip-dominant in their movement strategies, which are insights that could suggest implications for injury risk and performance optimization.

Understanding these patterns allows for targeted interventions rather than generic programming.

We explored how to use assessments not just to collect numbers, but to build comprehensive pictures of athletic capabilities and limitations that directly inform programming decisions.

The foundation starts with jump testing, but not just any jump testing—systematic assessment using multiple jump variations to understand different qualities.

We used basic force deck outputs including jump height, peak force, and reactive strength index (RSI), but the magic isn't in the individual numbers—it's in understanding their relationships.

For instance, comparing an athlete's squat jump (no countermovement) to their countermovement jump tells you about their ability to utilize the stretch-shortening cycle. If the difference is minimal, that athlete likely needs work on elastic/reactive qualities.

If the difference is large, they're already efficient at using stored elastic energy and might benefit more from pure strength development.

Emphasis on the word "might" is important because depending on the context (what sport does this person play) then general assumptions will likely change.

However, the data serves to elicit and lead that conversation so that the appropriate approach is discovered.

Movement dominance assessment was another crucial component.

Looking at what the intuitive "movement strategy" of the athlete played a role in:

A) understanding their default programming and

B) whether the shapes they chose were bio-mechanically efficient for the tasks that they were charged with.

We examined whether athletes are knee-dominant or hip-dominant in their movement strategies, which are insights that could suggest implications for injury risk and performance optimization.

Understanding these patterns allows for targeted interventions rather than generic programming.

The Eccentric Utilization Ratio:

A Window into Elastic Strength

The eccentric utilization ratio (EUR) deserves special attention because it's often misunderstood or underutilized in performance settings.

Simply put, EUR is the ratio between countermovement jump performance and squat jump performance.

But this simple calculation provides profound insights into an athlete's elastic strength capabilities.

When an athlete performs a countermovement jump, they're using the stretch-shortening cycle—the rapid eccentric-concentric coupling that stores and releases elastic energy. The squat jump eliminates this mechanism, relying purely on concentric force production.

The ratio between these two performances tells you how well an athlete can utilize elastic energy storage and release.

An EUR below 1.0 (meaning the squat jump is actually higher than the countermovement jump) indicates less disposition towards using stretch-shortening cycle function.

An EUR between 1.0 and 1.1 suggests limited elastic capabilities—these athletes would benefit from plyometric training, reactive work, and exercises emphasizing the amortization phase.

An EUR above 1.2 indicates good elastic function, and these athletes might benefit more from maximal strength or power development rather than additional plyometric work.

The programming implications are potentially significant, when coupled with context.

Instead of giving everyone the same plyometric program, you're tailoring interventions based on individual needs. The athlete with a low EUR gets progressive plyometric training starting with extensive jumps and building to intensive work.

The athlete with a high EUR might focus on heavy strength training or loaded jumps to improve force production rather than elastic qualities.

Simply put, EUR is the ratio between countermovement jump performance and squat jump performance.

But this simple calculation provides profound insights into an athlete's elastic strength capabilities.

When an athlete performs a countermovement jump, they're using the stretch-shortening cycle—the rapid eccentric-concentric coupling that stores and releases elastic energy. The squat jump eliminates this mechanism, relying purely on concentric force production.

The ratio between these two performances tells you how well an athlete can utilize elastic energy storage and release.

An EUR below 1.0 (meaning the squat jump is actually higher than the countermovement jump) indicates less disposition towards using stretch-shortening cycle function.

An EUR between 1.0 and 1.1 suggests limited elastic capabilities—these athletes would benefit from plyometric training, reactive work, and exercises emphasizing the amortization phase.

An EUR above 1.2 indicates good elastic function, and these athletes might benefit more from maximal strength or power development rather than additional plyometric work.

The programming implications are potentially significant, when coupled with context.

Instead of giving everyone the same plyometric program, you're tailoring interventions based on individual needs. The athlete with a low EUR gets progressive plyometric training starting with extensive jumps and building to intensive work.

The athlete with a high EUR might focus on heavy strength training or loaded jumps to improve force production rather than elastic qualities.

Dynamic Strength Index:

Bridging the Gap Between Testing and Training

The Dynamic Strength Index (DSI) represents another crucial assessment tool we explored in depth.

DSI is calculated as the ratio between ballistic peak force (typically from a countermovement jump) and isometric peak force (from an isometric mid-thigh pull or similar assessment).

This ratio provides insights into an athlete's ability to express their strength dynamically.

A low DSI (below 0.6) indicates that an athlete has significant strength reserves they cannot access dynamically. These athletes don't need more maximal strength—they need to learn to apply the strength they have more rapidly.

Programming should emphasize rate of force development, ballistic training, and velocity-based work.

Conversely, a high DSI (above 0.8) suggests an athlete is already efficient at utilizing their available strength dynamically.

These athletes would benefit more from increasing their strength ceiling through heavy resistance training rather than more power or speed work.

The DSI concept challenges the common assumption that all athletes need more strength.

Sometimes, the limitation isn't strength capacity but strength expression.

DSI is calculated as the ratio between ballistic peak force (typically from a countermovement jump) and isometric peak force (from an isometric mid-thigh pull or similar assessment).

This ratio provides insights into an athlete's ability to express their strength dynamically.

A low DSI (below 0.6) indicates that an athlete has significant strength reserves they cannot access dynamically. These athletes don't need more maximal strength—they need to learn to apply the strength they have more rapidly.

Programming should emphasize rate of force development, ballistic training, and velocity-based work.

Conversely, a high DSI (above 0.8) suggests an athlete is already efficient at utilizing their available strength dynamically.

These athletes would benefit more from increasing their strength ceiling through heavy resistance training rather than more power or speed work.

The DSI concept challenges the common assumption that all athletes need more strength.

Sometimes, the limitation isn't strength capacity but strength expression.

RSI and Plyometric Progressions:

Building Explosive Athletes Systematically

The sessions on reactive strength index (RSI) and plyometric progressions addressed one of the most common programming challenges: when and how to progress plyometric training intensity.

RSI, calculated as jump height divided by ground contact time, provides an objective measure of an athlete's ability to tolerate and utilize high-intensity plyometric training.

RSI, calculated as jump height divided by ground contact time, provides an objective measure of an athlete's ability to tolerate and utilize high-intensity plyometric training.

We explored a systematic progression model based on stretch-shortening cycle demands:

Level 1 - Extensive Plyometrics: Low intensity, longer ground contacts (>250ms), focusing on landing mechanics and basic force absorption.

Examples include repeated broad jumps, box step-downs, and extensive bounding.

Athletes at this level typically show RSI values below 1.5.

Level 2 - Intensive Horizontal Plyometrics: Moderate intensity with emphasis on horizontal force production. Ground contacts between 150-250ms. Examples include acceleration bounds, single-leg bounds, and horizontal reactive jumps.

Athletes progress here with RSI values between 1.5 and 2.0.

Level 3 - Intensive Vertical Plyometrics: Higher intensity with rapid stretch-shortening cycles. Ground contacts between 100-200ms. Includes repeated hurdle jumps, depth jumps from low boxes, and reactive jump sequences.

Appropriate for athletes with RSI above 2.0.

Level 4 - Shock Method Training: Maximum intensity with minimal ground contact times (<150ms). Includes depth jumps from heights above 60cm, complex reactive sequences, and weighted jump training.

Reserved for athletes with RSI above 2.5 and extensive training history.

The critical insight here is that progression isn't based on arbitrary timelines or subjective assessment—it's driven by objective capacity measured through RSI.

This prevents the all-too-common scenario of athletes performing high-intensity plyometrics before they have the reactive strength to benefit from them, reducing injury risk while optimizing adaptation.

Level 1 - Extensive Plyometrics: Low intensity, longer ground contacts (>250ms), focusing on landing mechanics and basic force absorption.

Examples include repeated broad jumps, box step-downs, and extensive bounding.

Athletes at this level typically show RSI values below 1.5.

Level 2 - Intensive Horizontal Plyometrics: Moderate intensity with emphasis on horizontal force production. Ground contacts between 150-250ms. Examples include acceleration bounds, single-leg bounds, and horizontal reactive jumps.

Athletes progress here with RSI values between 1.5 and 2.0.

Level 3 - Intensive Vertical Plyometrics: Higher intensity with rapid stretch-shortening cycles. Ground contacts between 100-200ms. Includes repeated hurdle jumps, depth jumps from low boxes, and reactive jump sequences.

Appropriate for athletes with RSI above 2.0.

Level 4 - Shock Method Training: Maximum intensity with minimal ground contact times (<150ms). Includes depth jumps from heights above 60cm, complex reactive sequences, and weighted jump training.

Reserved for athletes with RSI above 2.5 and extensive training history.

The critical insight here is that progression isn't based on arbitrary timelines or subjective assessment—it's driven by objective capacity measured through RSI.

This prevents the all-too-common scenario of athletes performing high-intensity plyometrics before they have the reactive strength to benefit from them, reducing injury risk while optimizing adaptation.

Transforming Theory into Practice:

Implementation Strategies

Integrating Perception-Based Training

Moving from traditional reaction training to perception-based training requires thoughtful progression.

Start by identifying the key perceptual skills in your sport.

In team sports, this might include reading opponent body language, recognizing tactical patterns, or anticipating space development. In individual sports, it could involve reading environmental conditions, opponent positioning, or tactical situations.

Next, design training activities that include these perceptual elements.

Instead of cone drills, use partner mirror drills where athletes must respond to human movement.

Replace predetermined agility ladders with small-sided games that require constant perception and decision-making. Incorporate constraints that force athletes to gather and process information before acting—for example, calling out tactical information while executing physical skills.

The progression should move from simple to complex perceptual demands.

Begin with single-opponent scenarios with limited options.

Progress to multiple opponents with increasing tactical complexity.

Eventually, approach full game-like scenarios where perception, decision-making, and execution must occur simultaneously under pressure.

Assessment becomes crucial here.

Traditional agility tests might not capture improvements in perception-based performance. Consider using video analysis to assess decision-making quality, reaction times to game-specific stimuli, or performance in representative test scenarios that include perceptual components.

Start by identifying the key perceptual skills in your sport.

In team sports, this might include reading opponent body language, recognizing tactical patterns, or anticipating space development. In individual sports, it could involve reading environmental conditions, opponent positioning, or tactical situations.

Next, design training activities that include these perceptual elements.

Instead of cone drills, use partner mirror drills where athletes must respond to human movement.

Replace predetermined agility ladders with small-sided games that require constant perception and decision-making. Incorporate constraints that force athletes to gather and process information before acting—for example, calling out tactical information while executing physical skills.

The progression should move from simple to complex perceptual demands.

Begin with single-opponent scenarios with limited options.

Progress to multiple opponents with increasing tactical complexity.

Eventually, approach full game-like scenarios where perception, decision-making, and execution must occur simultaneously under pressure.

Assessment becomes crucial here.

Traditional agility tests might not capture improvements in perception-based performance. Consider using video analysis to assess decision-making quality, reaction times to game-specific stimuli, or performance in representative test scenarios that include perceptual components.

Developing Your Observational Framework

Implementing Pfaff's observational framework requires discipline and systematic practice.

Start by selecting one movement pattern relevant to your coaching context—perhaps the acceleration phase of sprinting, the plant phase of cutting, or the approach phase of jumping.

Dedicate specific sessions purely to observation without intervention.

This is harder than it sounds—the coaching instinct is to correct immediately. But observation sessions allow you to build your visual database without the pressure of immediate feedback.

Create observation templates that guide your focus.

For each body segment, note specific checkpoints: position at key moments, range of motion, timing relative to other segments, symmetry between sides. Over time, these templates become internalized, and observation becomes more automatic.

Record video from consistent angles and review using your systematic approach.

Slow motion allows you to verify what you think you saw in real-time (also something that we did during Dan Pfaff's practical session...slow motion video analysis from multiple angles.)

Build a library of movement patterns—both efficient and inefficient—that serves as your reference database.

Most importantly, collaborate with other coaches to calibrate your observations.

Watch the same athletes and compare notes.

This inter-rater reliability check helps identify blind spots and refines your observational accuracy.

Start by selecting one movement pattern relevant to your coaching context—perhaps the acceleration phase of sprinting, the plant phase of cutting, or the approach phase of jumping.

Dedicate specific sessions purely to observation without intervention.

This is harder than it sounds—the coaching instinct is to correct immediately. But observation sessions allow you to build your visual database without the pressure of immediate feedback.

Create observation templates that guide your focus.

For each body segment, note specific checkpoints: position at key moments, range of motion, timing relative to other segments, symmetry between sides. Over time, these templates become internalized, and observation becomes more automatic.

Record video from consistent angles and review using your systematic approach.

Slow motion allows you to verify what you think you saw in real-time (also something that we did during Dan Pfaff's practical session...slow motion video analysis from multiple angles.)

Build a library of movement patterns—both efficient and inefficient—that serves as your reference database.

Most importantly, collaborate with other coaches to calibrate your observations.

Watch the same athletes and compare notes.

This inter-rater reliability check helps identify blind spots and refines your observational accuracy.

Building Effective Performance Teams

Creating role clarity within performance teams starts with explicit documentation.

Develop clear position descriptions that outline not just responsibilities but also boundaries.

Who makes return-to-play decisions?

Who has final say on training loads during competition periods?

Who communicates with athletes about sensitive issues?

Establish regular communication protocols that respect role boundaries while ensuring information flow.

This might include structured team meetings, shared documentation systems, or formal handover processes when athletes transition between team members.

Create decision trees for common scenarios.

When an athlete reports pain, what's the referral process?

When performance drops, who initiates the investigation?

Having these protocols established prevents confusion and ensures consistent, professional responses.

Foster a culture of professional respect where team members value each other's expertise. This means strength coaches deferring to physiotherapists on injury management, therapists respecting coaches' training periodization, and everyone recognizing the boundaries of their competence.

Develop clear position descriptions that outline not just responsibilities but also boundaries.

Who makes return-to-play decisions?

Who has final say on training loads during competition periods?

Who communicates with athletes about sensitive issues?

Establish regular communication protocols that respect role boundaries while ensuring information flow.

This might include structured team meetings, shared documentation systems, or formal handover processes when athletes transition between team members.

Create decision trees for common scenarios.

When an athlete reports pain, what's the referral process?

When performance drops, who initiates the investigation?

Having these protocols established prevents confusion and ensures consistent, professional responses.

Foster a culture of professional respect where team members value each other's expertise. This means strength coaches deferring to physiotherapists on injury management, therapists respecting coaches' training periodization, and everyone recognizing the boundaries of their competence.

The Bigger Picture:

Systems Thinking in Performance Coaching

What became crystal clear during my time at ALTIS is that excellence in coaching isn't about having all the answers—it's about having robust systems for finding answers.

Every concept we discussed, from perception-based training to data driven plyometric progressions, represents a systematic approach to solving coaching problems.

These systems serve multiple functions.

They standardize decision-making, ensuring consistency across athletes and over time.

They provide objective criteria for progression, removing guesswork from program advancement.

They create common language within coaching teams, facilitating communication and collaboration.

They enable continuous improvement by providing clear metrics for evaluation.

But perhaps most importantly, systematic approaches free cognitive resources for what matters most: connecting with athletes, observing subtle details, and making the creative adaptations that distinguish good coaching from great coaching.

When you don't have to think about what test to use or how to progress training, you can focus on how your athlete is responding, what they need emotionally, and how to optimize their individual development path.

This philosophy fundamentally underpins the reason I'm building Program Pro.

It's not about replacing coaching judgment with algorithms—it's about providing the systematic foundation that enables coaches to apply their judgment more effectively.

When the routine decisions are systematized, the important decisions get the attention they deserve.

Every concept we discussed, from perception-based training to data driven plyometric progressions, represents a systematic approach to solving coaching problems.

These systems serve multiple functions.

They standardize decision-making, ensuring consistency across athletes and over time.

They provide objective criteria for progression, removing guesswork from program advancement.

They create common language within coaching teams, facilitating communication and collaboration.

They enable continuous improvement by providing clear metrics for evaluation.

But perhaps most importantly, systematic approaches free cognitive resources for what matters most: connecting with athletes, observing subtle details, and making the creative adaptations that distinguish good coaching from great coaching.

When you don't have to think about what test to use or how to progress training, you can focus on how your athlete is responding, what they need emotionally, and how to optimize their individual development path.

This philosophy fundamentally underpins the reason I'm building Program Pro.

It's not about replacing coaching judgment with algorithms—it's about providing the systematic foundation that enables coaches to apply their judgment more effectively.

When the routine decisions are systematized, the important decisions get the attention they deserve.

Conclusion:

The Continuous Journey of Coaching Mastery

Teaching at ALTIS reminded me of something fundamental: coaching mastery isn't a destination—it's a continuous journey of refinement, learning, and systematization.

The best coaches aren't the ones who know everything; they're the ones who have systems for learning, frameworks for decision-making, and the humility to keep evolving.

The concepts we explored—perception versus reaction, systematic observation, role clarity, comprehensive athlete profiling—aren't just theoretical constructs. They're practical tools that directly impact athlete outcomes.

When we train perception alongside reaction, athletes make better decisions under pressure.

When we observe systematically, we catch subtle inefficiencies before they become major problems.

When we maintain role clarity, athletes receive optimized support from true specialists.

When we profile comprehensively, training becomes precisely targeted rather than generically applied.

But implementing these concepts requires more than knowledge—it requires systems.

Systems for assessment, for progression, for observation, for collaboration.

This is where the art and science of coaching converge.

The science provides the framework; the art lies in applying it with nuance, empathy, and creativity.

As you reflect on these concepts, consider your own coaching practice.

Where could systematic approaches enhance your effectiveness?

What frameworks would help you make better decisions?

How could clearer role definition improve your team's function?

These aren't just philosophical questions—they're practical considerations that directly impact your athletes' development.

Remember, the goal isn't rigidity—it's clarity.

Clear systems provide the foundation for creative adaptation.

They're not constraints; they're enablers.

They don't replace coaching intuition; they inform and refine it.

The journey toward systematic coaching excellence is ongoing, but the tools and frameworks exist to support that journey.

Whether it's implementing perception-based training, developing your observational skills, or building better performance teams, the path forward is clear: embrace systems, maintain curiosity, and never stop refining your craft.

Because great coaching isn't about having all the answers—it's about having the right systems to find them.

The best coaches aren't the ones who know everything; they're the ones who have systems for learning, frameworks for decision-making, and the humility to keep evolving.

The concepts we explored—perception versus reaction, systematic observation, role clarity, comprehensive athlete profiling—aren't just theoretical constructs. They're practical tools that directly impact athlete outcomes.

When we train perception alongside reaction, athletes make better decisions under pressure.

When we observe systematically, we catch subtle inefficiencies before they become major problems.

When we maintain role clarity, athletes receive optimized support from true specialists.

When we profile comprehensively, training becomes precisely targeted rather than generically applied.

But implementing these concepts requires more than knowledge—it requires systems.

Systems for assessment, for progression, for observation, for collaboration.

This is where the art and science of coaching converge.

The science provides the framework; the art lies in applying it with nuance, empathy, and creativity.

As you reflect on these concepts, consider your own coaching practice.

Where could systematic approaches enhance your effectiveness?

What frameworks would help you make better decisions?

How could clearer role definition improve your team's function?

These aren't just philosophical questions—they're practical considerations that directly impact your athletes' development.

Remember, the goal isn't rigidity—it's clarity.

Clear systems provide the foundation for creative adaptation.

They're not constraints; they're enablers.

They don't replace coaching intuition; they inform and refine it.

The journey toward systematic coaching excellence is ongoing, but the tools and frameworks exist to support that journey.

Whether it's implementing perception-based training, developing your observational skills, or building better performance teams, the path forward is clear: embrace systems, maintain curiosity, and never stop refining your craft.

Because great coaching isn't about having all the answers—it's about having the right systems to find them.

Copyright © Automated Strength Coach 2024